THE NAKED CITY: CRIME STORIES FROM THE BURBS

During the past two to three decades in Australia we have seen a rash of books and television programs focusing on the more notorious aspects of true crime. Ex-crims have cashed-in with sensationalised, ghost-written biographies, often more fiction than fact. Cold case TV shows have recruited former well-known police detectives in an attempt to re-examine unsolved murders, and mini-series have dramatized the so called ‘underbelly’. In his latest book, Suburban Noir, author Peter Doyle steers well clear of the tabloid approach that many of these docos and bios invariably adopt.

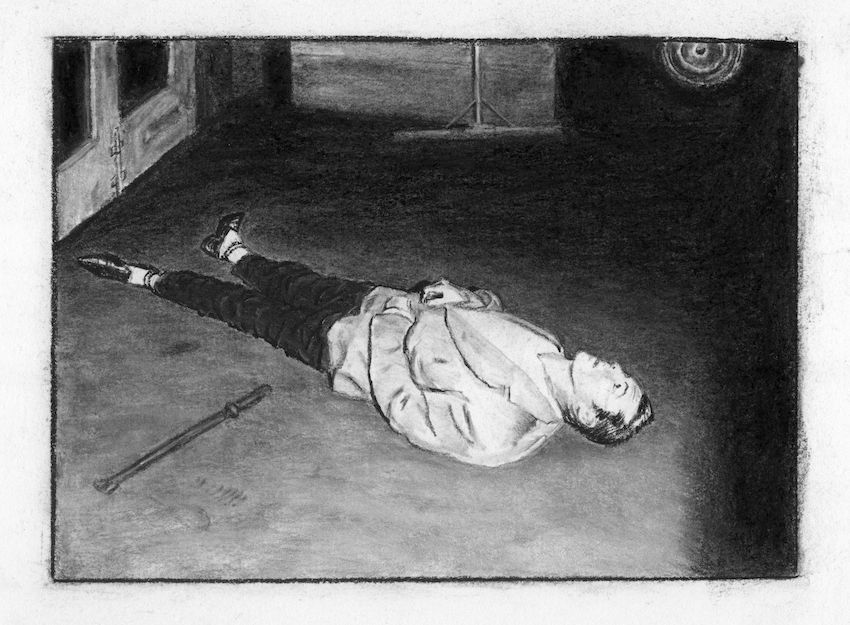

Doyle is not only a celebrated writer of crime fiction and winner of two Ned Kelly awards, but the curatorial saviour behind the publications City Of Shadows and Crooks Like Us, which brought to life a remarkable collection of forensic photographs from the archives of the Justice and Police Museum. Those images came from the first half of the 1900s but in his latest book he journeys deep into suburban Sydney during the ‘50s and ‘60s, for a highly engaging chronicle of “crime and mishap” – complete with numerous photographs and his own illustrations.

It was a project that first started in 2011 and Peter admits that progress was at first slow:

“The drabness of 1950s Sydney suburbia, the grim and depressing nature of everyday crime back then meant it was a bit harder to find anything for me to really come to grips with. But once I started digging deeper, I started to find hooks and themes that engaged my interest. As with any delving into historic crime, you can trust that some deeper weirdness will reveal itself, at least some of the time.”

The catalyst for the book clearly came from Peter’s uncle, the celebrated and exceptionally canny detective Brian Doyle, the focus of a number of chapters in the book, and the source of a fascinating and intriguing archive of forensic material from his personal backyard stash. He notes that the book is not a bio of his late uncle and that the predominant subject is crime, in all its various manifestations. However, his admiration for Brian Doyle as a scrupulously honest, decent and highly intelligent cop, shines throughout. Nevertheless, he points out:

“I really didn’t want to paint a monochrome picture of him. To my eye he had the strengths and failings of a basically decent middle class man of the time. And a pretty fierce natural intelligence. Like many of that time, he was able, like his brothers, to work out of slum background into comfortable and safe middle class life, without enjoying many chances to develop his talents the way we would expect now.”

It was Brian’s son and Peter’s cousin Stephen who alerted Peter to the plastic shopping bags containing his uncle’s extensive archive, which has generated much of the material in the book. As one of the first real celebrity cops, Brian was involved in two of the most widely publicised cases of the ‘50s and ‘60s – the Kingsgrove Slasher and the ransom/murder of schoolboy Graeme Thorne. Whilst a large section of the book deals with Brian, there are numerous other crimes and mishaps detailed, all recalled with Peter’s photographic eye for detail and what must have been endless hours wading through newspapers and police records.

Given that Peter is an established crime novelist, I asked him whether he sometimes found himself slipping into the vernacular and style of the fictional. He pointed out:

“Yes, the same rules apply, but I try to resist the urge to be too hardboiled or street smart in the telling. These were real events that involved real suffering for real people, so a certain seriousness is called for. But crime is often sort of funny too — absurdly, sadly so. And that needs to be acknowledged as well. I hate the fake seriousness, earnestness of so much modern true crime.”

Suburban Noir is definitely a book that will resonate differently with various age groups, especially if you grew up in the burbs of Sydney. If you are sixty plus then you may well recall the ‘Slasher’ and the Graeme Thorne kidnapping, cases which captured the front pages of the tabloid press for weeks on end. The streetscapes, the lonely hotel rooms and the social mores of the day are all lucidly painted and recalled with Peter’s keen eye for not only the obvious but the incidental.

On the other hand modern day millennials, daily confronted with stories of crooked cops, vicious drug gangs, violent family feuds and increasing gun crime might be somewhat bewildered (albeit entranced) at the nature of crime during the ‘50s and ‘60s. Not that there wasn’t bloodshed and mayhem back then, but many of the crimes were married to the times – some of them tragic but others laughable by today’s standards.

These days delinquent youths break into suburban houses, steal the car keys and take the family BMW for a joy ride. It’s hard to believe their counterparts in the early ‘50s would bother snatching the one or two shillings left out to pay the local milkman but that was the case in one Sydney suburb. Peter recalls the episode where an unnamed citizen rigged up an ingenious trip camera (a Box Brownie indeed) and flash to catch the perpetrator. The accompanying photo of a young lad, just about to grab the coins, is an absolute classic and eventually led to him being nabbed.

Through his painstaking curatorial work at the Justice and Police Museum and endless other research, Peter has long had a fascination with crime scene photos, something he reflects on with great eloquence in the book. Whether they portray a fatal accident or a grisly murder he sees them as “a mystery wrapped in an enigma”, explaining:

“On the one hand they’re grimy, awful, blank, completely non-aesthetic, anti-beautiful and so on, which makes them in a way nearly perfect! There’s no sentimentality there, no attempt to manipulate the viewer, no doffing the cap to current visual artistic trends: there’s the sort of purity of intention there that artists strive for. And police photos are mostly concerned with real things, important things – even though the vast majority are nearly completely forgotten. They were matters that caused an interruption in the flow of everyday events back then: a robbery, an assault, an ‘offence’. Disruption, which I guess is a major subject matter of ‘Art’.”

Apart from the numerous photographs, Peter has also illustrated the book with a number of his own highly evocative pencil and ink wash drawings, many of which will be on exhibition at the launch on Saturday 5 November at 2pm at the Rogue Pop-Up Gallery, 130 Regent St. Redfern. All are welcome. The exhibition stays open for a couple of weeks thereafter and the drawings are also for sale.

For a really interesting insight into the book, check out Peter’s short film Slasher Patrol: