Behind the Story: Retelling Isolde & Tristan

By HOPE PRATT

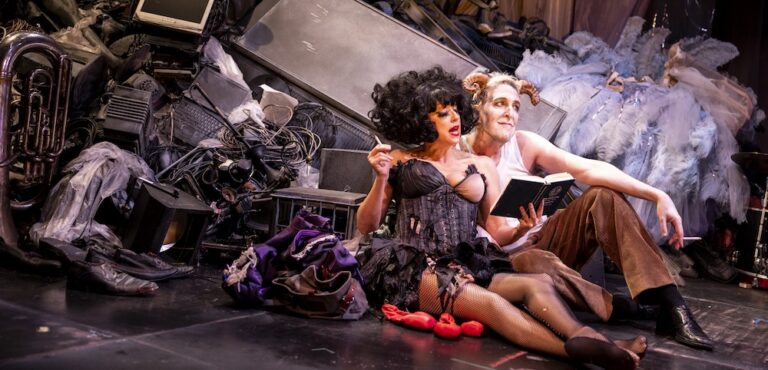

Following the announcement a retelling of Wagner’s opera Isolde & Tristan will be hitting the stage at The Old Fitz Theatre this May, City Hub sat down with director, Damien Ryan, and actors Emma Wright (Isolde) and Tom Wilson (Tristan), to talk about what it meant to put on Wagner’s epic in a shoebox.

In a back alleyway behind St Peter’s Parish in Surry Hills, a small courtyard opens up. Tom Wilson (Tristan) wanders in circles balancing a stick on his forefinger as Emma Wright (Isolde) shows me the way in.

Soon, director Damien Ryan appears with the keys, and we can enter the small brick chapel where the cast and crew of Sport for Jove’s Isolde & Tristan rehearse. Barely the size of the stage they’re to occupy in a week, the space is tiny, strewn with costume racks and props, it feels like stepping back in time. A suitable atmosphere to rehearse in when your play spans 1000 years.

“I think it’s one of the archetypal stories of love, and love as a curse,” Ryan says, leaning back in his chair with his arms crossed. “Love remains synonymous with pain.”

This is what stands out about Esther Vilar’s intimate retelling of the famous Arthurian legend turned operatic epic by Richard Wagner. It’s also why it feels timeless.

While not an all-out opera, Vilar blends conversation and music to follow the story of two enemies: Princess Isolde of Ireland and Tristan Knight of Cornwall, as they travel across the Irish sea to meet King Marke, Isolde’s betrothed. It’s in the confines of the tiny boat that tensions arise as the two come face to face with the symmetry of love and pain.

“Almost all the great love myths were all about how love can be a forbidden thing, but also love can be a painful thing,” Ryan explains. “The tale is about enemies loving each other. So, in many ways it could not be more relevant.”

It’s a story as old as time. Star-crossed lovers, from ancient grudges where civil blood makes civil hands unclean, and yet in this iteration, love does not bury conflict. According to Ryan, this story uses the original opera’s theme of ‘Liebestod’ – love death – to show a stark realisation of humanity across divides.

“That’s what the love myth is about. Isolde and Tristan are really just human metaphors for why we can’t love each other, why we can’t solve our geopolitical conflicts, our cultural conflicts.”

In Vilar’s retelling it is not as simple as Isolde falling in love with her oppressor, instead she becomes a revenger. This is what ended up being Wright’s favourite part about taking on the role of Isolde; the script was able to breathe new life into her character, to give her a new purpose.

“I love that the play empowers her as an individual and allows us to see an alternative version of events in which she’s not just a lovestruck woman, but she’s someone who has a greater calling.”

Wright goes on to explain that retelling myth is an opportunity to give characters previously overlooked by history and legend alike a chance to stand on their own or at least in a new light.

“When I started to research Isolde, it was hard to get a grip of who she was as a woman outside of the men that she is attached to. So, I love opportunities to look back at myth and legend. How if we would have placed [this story] in a contemporary world, what would happen to the female stories?”

Wilson chimes in after Wright finishes, leaning forward in his seat and clasping his hands in front of him. For him, Vilar also sheds new light on Tristan as the leading man, allowing him a vulnerability previously untapped.

“I found it quite interesting, on a personal level, what’s expected of Tristan and the circumstances that he’s thrust into. Across this journey is him discovering that you know, as Isolde is not just the damsel, he’s not just the hound.”

Hearing about the grandeur of the story, it seems odd to put it on somewhere like The Old Fitz Theatre. I would have expected somewhere a little bigger.

When I ask about it, Ryan just chuckles. Because it’s the space that provides a potency to bring the story to life.

“The music changes everything,” Wilson adds. “It takes the imagination to a completely different place.”

Wright nods at Wilson. “What I love about The Fitz is that it’s an intersectional point between intimacy and the epic.”

“It’s like a highly concentrated Irish whiskey.” Bryan says and we all laugh.