Ben Quilty on Myuran Sukumaran and “Another Day in Paradise”

It’s not two years since Andrew Chan and Myuran Sukumaran were executed on Nusa Kambangan Island. Chan, reportedly wearing his favourite Penrith Panthers jersey, led the group in a rendition of ‘Amazing Grace’, but before they finished their lives were ended in a brutal hail of gunfire. The final picture was a far cry from the scenes that accompanied their arrest and conviction for drug trafficking a decade earlier. Chan, the mastermind, and Sukumaran, the strong man – or at least that’s how they were then portrayed by the media.

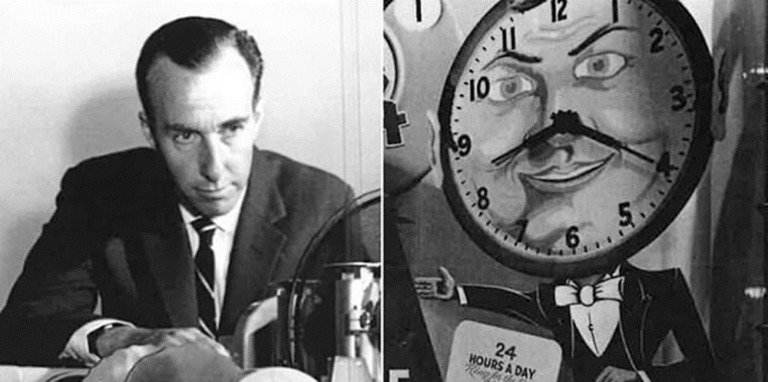

For Ben Quilty, who became a close friend and mentor to Sukumaran, the experience is admittedly still pretty raw: “I’ve never been through anything like that in my life. I kind of understand what grief is now. It’s different to what I thought it would be, that’s for sure.”

As Quilty puts the finishing touches on an exhibition of Sukumaran’s paintings for the Sydney Festival, it is with a conscious sense of honour and privilege in finishing what his friend began: “I’ve got a job to do. I promised Myuran that I would get this show up for people to see, which is what he wanted and what he deserves.”

Quilty, who came to prominence for his Archibald-winning portrait of Margaret Olley, and then more recently as official war artist for the Australian Defence Force in Afghanistan, is perhaps Australia’s best known contemporary artist. He was also one of the most prominent advocates for Chan and Sukumaran, calmly and passionately opposing their death penalty. As an artist, Quilty is deeply conscious of the power of art to create an ongoing legacy, one that can outlast a person and perhaps even right some wrongs:

“If someone had written down my life’s achievement and my legacy when I was 21-years-old, it would be pretty dark, pretty self-indulgent,” said Quilty. “I’d been arrested, there were lots of drugs and alcohol – I was off the rails.”

Sukumaran was in Kerobokan at much the same age, and yet his mistakes were to be punished fatally and completely. Quilty can’t help but draw the comparison: “Myuran became a very humble, quiet, introspective, [a] very intelligent young man. He had created an amazing body of work and his legacy needs to include that at the end of his life rather than just the bad stuff.”

“I know I made some gross mistakes as a young bloke, self-indulgent idiocy really, and one of the worst things is you have this horrendous guilt about what you put your family through. Myuran’s guilt was that times a hundred, and he had to live with that guilt, but I think this exhibition will be an occasion where his family can be very proud of what their son achieved.”

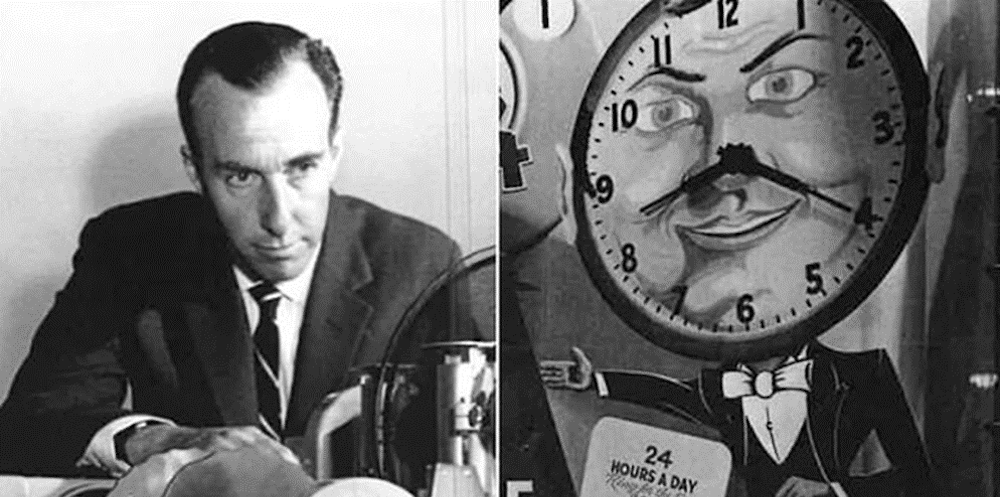

The title of the exhibition, Another Day in Paradise, is both ironic and bittersweet. Quilty agrees that there is a dark side to the title, but it is more a reflection of Sukumaran’s sense of humour – that he could laugh at himself and the insanity of the situations that he kept finding himself in. The title originally appeared as the subject line of an email Quilty received from Sukumaran following a riot inside Kerobokan prison. Having set up the education facility and art studio, Sukumaran had negotiated to gain access to the medical facility, so as to drug test his students. “He was worried that if people were found to be using drugs inside the facility, the guards would rightly shut it down,” explained Quilty. “When a riot happened inside the prison shortly after, he sent me these unbelievable photos of a man who had been hit in the arm with a machete. Myuran had stitched him up and that was the headline of the email, ‘Another Day in Paradise’.”

Chan and Sukumaran’s personal transformation throughout their time in Kerobokan was striking. Chan’s conversion to Christianity and founding the church within the prison, along with Sukumaran’s work in establishing the educational facility and art studio, was met with cynicism in some quarters – and yet that they were radically changed is really beyond question. Quilty, surprisingly, attributes much of this to the Indonesian prison system itself.

“You know, I don’t think there was ever enough written in the Australian media about the facility of Kerobokan prison. It enabled these young people to rehabilitate themselves and if they had any ideas, any dreams or goals, the guards, by negotiation, would always help them facilitate it. The better you behaved, the more privileges you would get. That was very real and I saw it with my own eyes. I think the Indonesians were never given the credit they were due for that. It’s just that the final punishment was so grotesque and archaic.”

While the lead up to Chan and Sukumaran’s execution saw many advocate – and sometimes at the highest levels – for the death penalty to be stayed, it also revealed some troubling fractures within the Australian community. Some for example argued that Chan and Sukumaran having made their mistakes should therefore face the consequences. Quilty, now as then, has been vocal in his opposition:

“I am part of a community who believe that you should stand up for human rights wherever, but particularly if they’re our own citizens. We need to stand up for them. We don’t need to declare war on Indonesia, but we definitely need to stand up and say that we disagree and we strongly disagree with what they’re doing.”

Perhaps equally troubling is Quilty’s belief that there were racial undertones in the way Chan and Sukumaran were treated by the Australian media. “I think that if Myuran and Andrew had happened to have been white, Irish descendant boys, like me, things would have been slightly different. Andrew was of Vietnamese heritage, Myuran was Sri Lankan, and they were treated in the Australian media through that lens. People deny it but I disagree. There were other people in that prison who had a very easy time with the Australian media.”

Along with Sukumaran’s moving and often disturbing paintings, Quilty and co-curator Michael Dagostino have rounded out the exhibition with a range of works by other artists. The common thread is that they are all from multicultural and marginalised backgrounds. As an exhibition, Another Day In Paradise picks at issues that are complex and loaded – matters of forgiveness and compassion, redemption and change, the human condition, the barbarism of state sponsored killing, and of what we want to be as a society. It’s about initiating and continuing a conversation about matters that might have been otherwise taboo.

“I don’t ever say that people shouldn’t have the right to say what they think and feel, but I equally have every right to disagree,” said Quilty. “This exhibition is a really important and healthy way to talk about things that have caused anguish on part of the community, on two families very directly, and on all the people who have supported them and become friends with them.” (GW)

Jan 13–Mar 26, 10am–4pm. Campbelltown Arts Centre, 1 Art Gallery Rd, Campbelltown. Free. Info: www.sydneyfestival.org.au/2017/myuran