The conversion of truth

BY BIWA KWAN

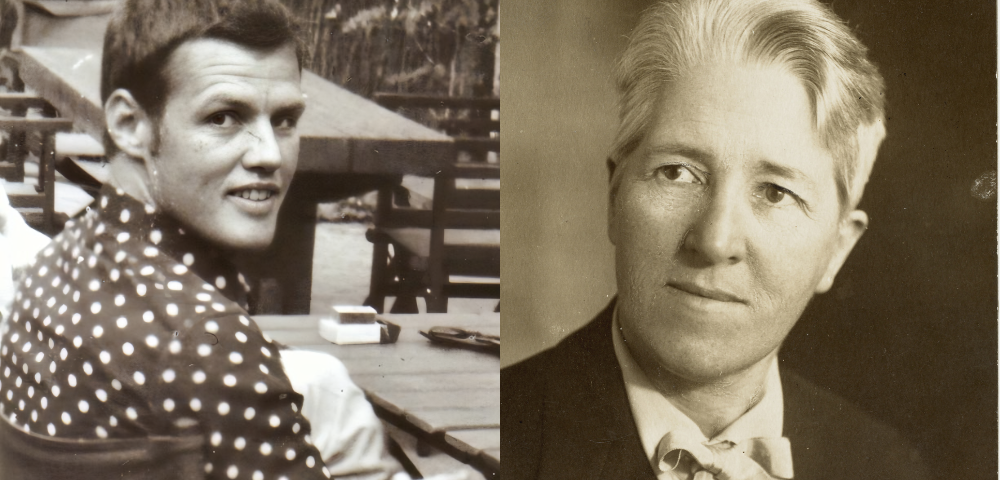

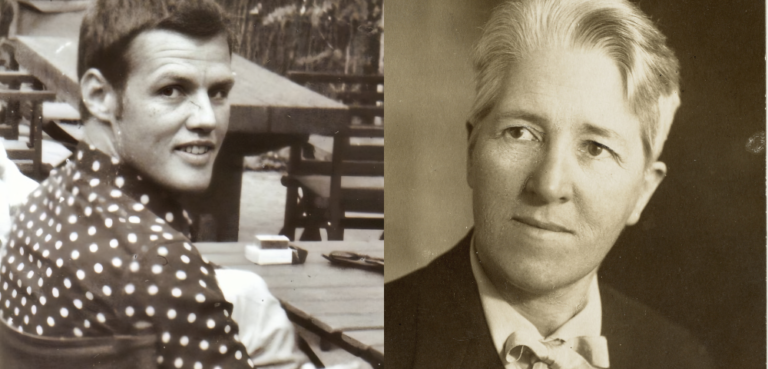

In 2005, Melbourne film school graduates Melissa Maclean and Luke Walker were driven by an intense curiosity to find out about the rising popularity of self-help groups. One in particular had attracted a deluge of media coverage ‘ Kenja and its co-founder Ken Dyers.

“We saw Ken being arrested for the first lot of sexual assault charges and we thought it is really interesting how Kenja keeps being called a cult, but when you look on the website it just looks like a self-help group,” says Maclean.

“And at the time I had some friends who were trying to work out what was going on in their lives, maybe not through a traditional therapy way, like I had a friend who went to Landmark, and I thought it was really interesting how we have these groups that don’t really look religious on the outside, but maybe there is something going on underneath.”

What the pair uncovered over a year of interviewing 30 people became the subject of the documentary Beyond Our Ken, screening on ABC TV on Sunday.

Walker attended Kenja for six months prior to Maclean getting on board to begin shooting the project.

“He was talking about how a direct approach needed to be made and an interview done, so at that point I said: ‘all right I could probably give that a go’ and wrote a letter to Ken and Jan and thankfully they decided they were happy to do an interview.”

The pair aimed to cover the trial from different perspectives, which consisted of going to Ken and Kenja first, then to former attendees and then giving Kenja the right of reply.

During the interviews, Walker and Maclean had come across a number of people who had been severely affected after being cut-off from the group. These individuals had been involved quite heavily, with almost every day in the week filled with Kenja activities from meditative-like ‘energy conversion’ sessions to eisteddfods and sport competitions.

One of the more heart-rending cases in the film concerns Cornelia Rau. Interviewed as part of the documentary, her erratic behaviour led to her expulsion from the group. She was shortly after wrongfully detained by Australian immigration and was later found to have paranoid schizophrenia.

Other cases mentioned in the film include 17-year-old Michael Beaver, who committed suicide, and Richard Peale, who later went missing. Both suffered from schizophrenia. The film claims the former was ejected from the group after having sex with a prostitute on the advice of his brother and the second did not respond well to a nude energy conversion session which brought up memories of a sexual assault in his childhood.

Just 10 days before the film was to premiere at the Melbourne International Film Festival Kenja’s founder, Ken Dyers, committed suicide with a gunshot to the head.

Dyers had been facing charges of sexual assault for the last decade. In 1993, 11 charges were laid against him, yet he was acquitted. In 2005, 22 charges concerning two 12-year-old girls were made. On July 25, 2007, Dyers took his own life after the police requested an interview based on fresh allegations by another girl.

The film almost did not premiere when Kenja contacted the selection committee for the festival requesting that the film be withdrawn.

“I think the Melbourne Film Festival, thankfully, made their own decision that it was a worthy film and to show it’ The idea that film is repressed, because the organisation itself is fighting against it, I think would be a terrible state of affairs for Australia,” says Maclean.

The film builds climatically to the finale where Dyers composure finally cracks and he launches into a seven-minute tirade. “They’re liars! I don’t have to prove that. I might have to prove that to God, but I don’t have to prove it to anyone else,” he says in the film.

The film is ultimately about awareness, says Maclean: “What we’ve tried to do with our film is make it a little bit of an awareness exercise as well so people can spot the groups that are going to exert a little more influence than you might expect.

“We’re not coming to it from the place that oh, only stupid people get involved in these types of groups. [It is] much more important to understand that really anyone at some point in their life could be vulnerable to this sort of a group.”