Teachers risk jail to tell refugee rancour

BY CHARLOTTE GRIEVE

On the evening of Sunday August 21, three Australian teachers risked two years’ imprisonment by speaking out about their experiences on Manus Island and Nauru.

Section 42 of the Border Force Protection Act has been controversial for creating a veil of secrecy around Australia’s billion-dollar offshore processing centres. This section criminalises “entrusted persons” from disclosing information about the conditions of the camps.

The event was organised by Teachers For Refugees, an an alliance of educators campaigning against the indefinite detention of asylum seekers.

“We are standing behind our professional values that tell us that this is wrong,” said Rachael Jacobs, an organiser of the event.

Speaking on the night was Judith Reen, a registered teacher and trained child protection worker with over 17 years’ experience working with children both in Australia and overseas.

Ms Reen has spent over two years working in Australia’s offshore processing centres.

“It changed the way I see the world,” she told a packed out room. “I feel I have a duty to do this.”

Ms Reen began by explaining her frustration with the lack of change in the conditions of the camps despite a Senate Inquiry and the filing of thousands of incident reports.

“This is why we are here today,” she said.

Upon arrival on Manus Island in November 2013, Ms Reen received an orientation training session where she learnt how to “quickly cut a bedsheet noose with a slip knife” in clear view of the detainees.

Her ability to teach was undermined by the lack of proper facilities. At times, she would teach between 50 and 60 people in a cement hallway.

“In Delta, there were no classrooms…no books, no chairs, no walls,” she said.

There were “ridiculous student teacher ratios” which made it “impossible” to meet their language needs.

Classes were regularly interrupted by raw sewerage that would flood the camp every time it rained and diesel and insecticide fumes used to control the mosquito population.

“You could track the decline [of the detainees] over months let alone years,” she said.

Ms Reen also spent 18 months teaching on Nauru, an island she describes as “in tatters” and rife with corruption and lawlessness.

She experienced frequent notifications of suicide attempts, children as young as four responding to their individual boat numbers and detainee’s beds being permanently infested with rats.

The majority of her students were on anti-depressants, sleeping tablets and anti-psychotics.

“They were given pills in a small cup through a trap door,” she said.

“Healthy children have to be proscribed serious medication to cope.”

Also speaking at the event, Jennifer Rose started her teaching placement on Nauru in November 2013. She expected the job to last for only a couple of months in the anticipation that the camps were temporary and would soon be closed. Almost three years later, the camps remain.

“Think about what you’ve done in the last three years,” she told the crowd.

Ms Rose spoke about widespread deterioration of mental health amongst the detainees as a result of poor living conditions. Up to ten families would share a single tent that would reach temperatures of up to 30 degrees Celsius for extended periods of time, she said.

In her first briefing, Ms Rose was told these camps were set up “to be a deterrent and it was working.”

She argued that the Australian government’s employment of private contractors such as Wilson Security and Save The Children allowed for blame to be shifted when “something goes wrong.”

“Countless reports show that detention causes depression and affects mental health but somehow it was Save The Children’s fault,” she said.

She made the point that sexual assaults were in fact under-reported as detainees were worried their asylum applications would be affected. And those reports that were filed to the police were routinely misplaced.

She said there was a “lack of forward thinking” in the running of camp schools. In her first five months on Nauru, the location of the school changed five times.

“This can be very disturbing for a child,” she said.

Eventually the camp schools were closed and children were transferred to local schools where corporal punishment is still implemented.

“There were issues around teacher attendance, cleanliness and hygiene, dogs in the school.”

Teacher Evan Davies then showed a number of rarely seen photographs displaying the militarised nature of the camps and the unhygienic conditions of local schools.

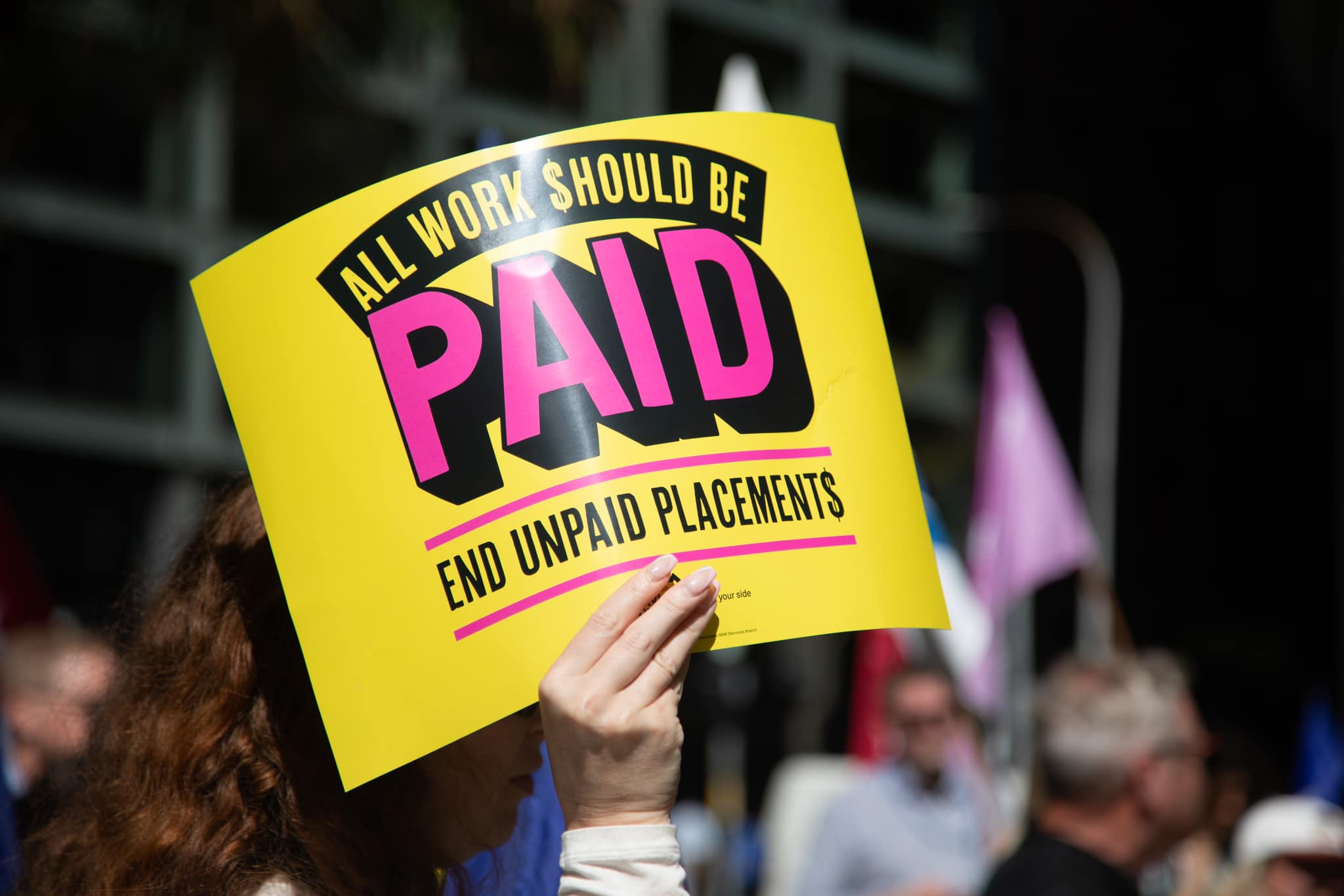

Teachers For Refugees has been organising community events to educate the public on the inhumane conditions faced by asylum seekers on Australia’s offshore detention centres.

They are working in conjunction with Doctors For Refugees and the Refugee Action Coalition to organise a street protest this Sunday August 28th starting at Sydney Town Hall at 1pm.