PHILLIP JOHNSTON & THE GEORGES MELIES PROJECT

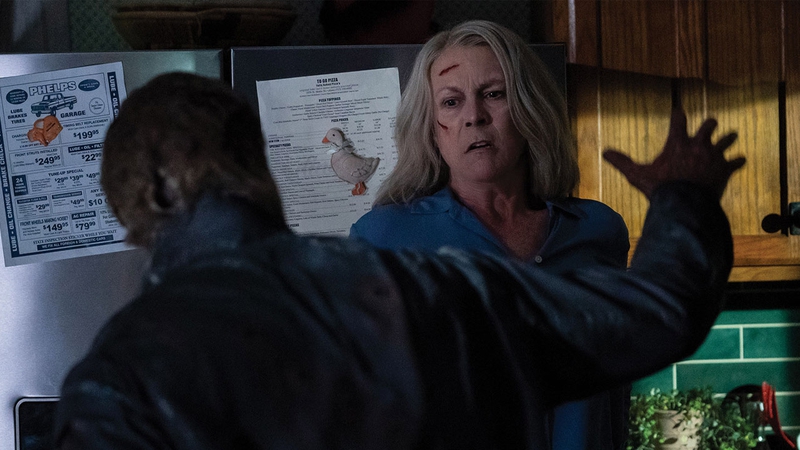

In the latest instalment of the Sydney Opera House’s Screen Live series, the ‘H.G. Wells of the jazz world’ enters into a dialogue of sound and vision with the world’s first ‘cinemagician.’ Avid cinephiles will relish this rare event, which marries a handful of recently-restored silent films produced by Frenchman Georges Méliès between 1896 and 1912 with live musical accompaniment from a local ensemble led by avant-jazz composer and saxophonist Phillip Johnston. Heavily influenced by his earlier forays into stage magic, Méliès enveloped his playful shorts with elements of fantasy, automata, alchemy and visual subterfuge, whilst birthing a number of sophisticated techniques, which have become hallmarks of contemporary film vernacular. Johnston, a veteran of the underground New York music scene, explains that his compositions – a cocktail of classical, jazz and experimental influences – ‘fuse’ with Méliès’ films to provide for an entirely unique sensory experience. “I don’t try to do quote-unquote ‘silent film music,'” Johnston explains, “I’ve tried to create a dialogue between a contemporary artist, i.e. me, and an artist from a 100 years ago…for a real fusion of the two in a new event, which is neither just film, nor just music.” The program includes eight short films: La Danse Du Feu, The Melomaniac, The Mermaid, The Damnation of Faust, Trip to the Moon, Hydrotherapie Fantastique (The Doctor’s Secret), The Merry Frolics of Satan and Voyage Across the Impossible.

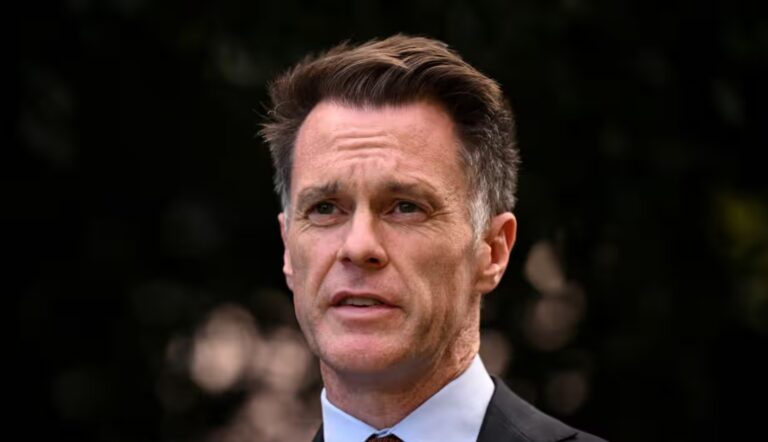

Chicago ex-pat Phillip Johnston spoke to City News from his Sydney home about his experience composing for silent films, his affection for ‘obsessive’ French filmmaker Georges Méliès (1861-1938), and his work on the Georges Méliès Project.

What inspired you to compose music to accompany a handful of short films, which were directed by Frenchman Georges Méliès more than one hundred years ago?

I’d been a fan of Georges Méliès’ work for a very long time. Geez, it must have been in the early 1970s, while I was living in San Francisco…I used to go to silent film screenings at this place, one of those repertory houses that were so great, but we don’t have anymore. Méliès films in particular really captured my imagination in the beginning, because of their fantastical quality. I’m really drawn to films where the artists have a kind of obsession with certain things and Méliès was nothing if not obsessive. Again and again his films tell me stories about devils, nymphs, mischief-makers and women as angels, which I thought was fantastic. His films are also very involved with magic, because he started his career as a magician and, initially, his films were a kind of an adjunct to his magic act, which he ran at the Robert-Houdin Theatre in Paris. I was really drawn to that aspect. Plus, the special effects, which are done with cardboard, pasteboard and glue, are so fantastic. I love things that are kind of homemade and funky looking…and yet Méliès’ films were also incredibly sophisticated because he was basically inventing all these techniques as he went along. So his films are right on the borderline between innocence and sophistication.

What flavour were you trying to capture with the music you composed for the Project?

That’s a very difficult question to answer because there are eight films that range from one minute long to twenty minutes long. The Georges Méliès Project wasn’t my first original score for a silent film project. The first was for a film called The Unknown (1927) directed by Tod Browning and starring Lon Chaney and a 19-year-old Joan Crawford in her first film appearance. It’s an amazing film. But when I decided I wanted to do a second project, I decided I wanted to do a series of short films so that I could experiment with different ideas about the relationship between music and film. As a result, the material that accompanies each of the short films in the Georges Méliès Project varies quite a bit. Some it has elements of jazz. Some of it is more like 20th Century classical music. One of the scores for example is based on thematic material from a Chopin Waltz. On the other hand, some have polkas in them. So, the music covers a wide variety. It also evokes styles from the era of silent film. This doesn’t at all mean that they’re conventional rag-time or turn-of-the-century piano scores, but they reference different kinds of music, which we associate with an earlier time, but in a kind of more complex fashion. So, small elements of the scores are reminiscent of an earlier era, but as a whole they’re quite modern.

Do you think your musical scores have altered the tonal quality and meaning of each of the eight Méliès films showing?

Absolutely. My particular approach to original scores for silent films is somewhat unconventional in that I try to reinvent the films in a different way. My scores attempt to be a true marriage of the past and the present because we can never see a silent film the way it was seen by the filmmaker or the people who saw it at the time. Everything that has happened over the last one hundred years has irrevocably altered our perception of the films we look at, so I don’t even try to do quote unquote ‘silent film music.’ What I’ve tried to do is create a dialogue between a contemporary artist, i.e. me, and an artist from a hundred years ago…for a real fusion of the two in a new event, which is neither just film, nor just music.

The Georges Méliès Project first premiered in 1997 at New York’s Lincoln Centre and since then you have toured with it across the US and Europe to much acclaim. Why do you think it has had such longevity?

People are tremendously interested in these silent films and original score projects for a couple of different reasons. For one, there is this incredible body of work from silent film era that had grown to a very sophisticated point before it was eradicated by the arrival of sound film. Many people think that film took a major step backwards when sound came into film because in a sense they had to start all over…of course they came forward from that as well. But there is this tremendously rich body of work that people are not aware because they don’t have access to them. Even thirty years ago you could see silent films on TV during the day, but now you don’t see them at all. So when people see films like Nosferatu (1921), Faust (1926), The Cabinet of Dr Caligari (1920) and Birth of a Nation, they are totally blown away because they are just incredible.

With Méliès’ films, I believe they appeal to modern audiences because so many things that he invented have become part of the film culture. It’s like when you go to a Shakespeare production and you hear lines that have just been absorbed into the culture and you go, ‘Ah, that’s where that comes from.’ So in a way Méliès’ films are unfamiliar, but when we see them we feel we’ve known them all our lives.

Finally, there’s a tremendous excitement to have live music with film. In a way, it’s kind of a balancing act or a circus performance because it’s very challenging to perform a written score and stay in sync with the film…so live musical performance mixed with the rich treasure of amazing films that people are just discovering for the first time. I think that’s why people are so excited about these performances.

Aug 22, Playhouse, Sydney Opera House, $20-29, 9250 7777, sydneyoperahouse.com