UNSW Endometriosis Research Funded By Gambling Giant Family

A donation of $50m towards “revolution[ising] endometriosis research” has public health researchers in an ethical quandary after learning the money was the result of investment in the gambling industry.

Last month, the Ainsworth family committed $50 million over 10 years to establish the Ainsworth Endometriosis Research Institute, which UNSW says will position Australia as a global leader in women’s health and the fight against endometriosis.

Three generations of the Ainsworth family have supported the endeavour, including centenarian Len Ainsworth, who founded Aristocrat Leisure in 1958, which would go on to become the world’s largest poker machine manufacturer.

A public health crisis in its own right, gambling losses on NSW poker machines have hit a record high, with pubs and clubs raking in $8.64 billion in revenue over 2024.

An analysis of state government data by Wesley Mission show $2.17 billion was lost to poker machines in NSW alone throughout the first 90 days of this year.

In a now deleted LinkedIn post seen by Guardian Australia, Andrew Hayen, a professor of biostatistics at University of Technology Sydney said that although endometriosis research is “long overdue”, he felt it important to consider the “ethics of investment”.

“Poker machines are a key driver of gambling addiction, financial distress, family violence and mental ill health,” he wrote. “These harms are not abstract. They are experienced every day by individuals and families, many of them women.

“There is no doubt that more funding is urgently needed for endometriosis research. But accepting philanthropic donations sourced from an industry built on public harm creates a troubling contradiction.

“It is hard to imagine any university in Australia today accepting donations from the tobacco industry. We should apply a similar level of scrutiny here.”

However, others argued researcher’s primary “moral obligation must be to the patients suffering today”.

“The women waiting years for diagnosis don’t have the luxury of perfect funding sources, they need solutions now,” Feroz replied in a comment to Hayen’s post. “With proper research safeguards in place, this funding could have a tremendous positive impact on the lives of women.”

Deciding on the lesser evil

Almost 1 million people across Australia suffer from endometriosis, with almost one in seven women impacted by the disease by age 49. This year, the World Economic Forum named it one of the nine diseases most affecting the lives of women, their communities and the global economy.

A spokesperson from UNSW said all donations were assessed through the university’s gift acceptance policy, which takes repetitional, ethical, and legal factors into consideration.

UNSW said in May that the $50m pledge is the largest known philanthropic contribution to endometriosis research globally and women’s health in Australia, as well as the largest philanthropic donation ever received by the university.

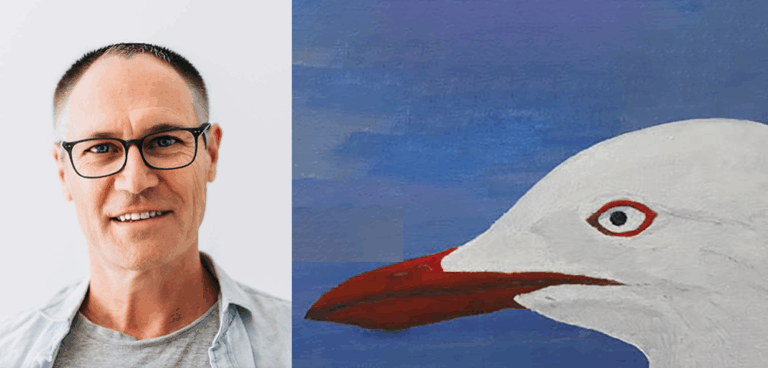

For descendant of Len Ainsworth, Lily, who has been experiencing pain from endometriosis since she was 15, the research is personal.

“While my fertility hasn’t been impacted, I experience chronic, daily pain and severe flare ups that debilitate me for days or weeks on end,” she said when the pledge was announced.

“Like many others, endometriosis has affected my education, my career, my relationships, my family, and dictates how I go about each and every day. This reality is shared with millions of people living with endo around Australia and the world.”

However, with an absence of funding for women’s health, and academia more generally, some people feel as though they’re left with little choice but to take the money.

“Sadly, with the current funding decline for science in Australia, all universities and the government see philanthropic investment as the best possible way to continue funding scientific research,” commented UTS academic Poppy Watson. “In reality, aren’t most incredibly wealthy donors rich off someone else’s back?”