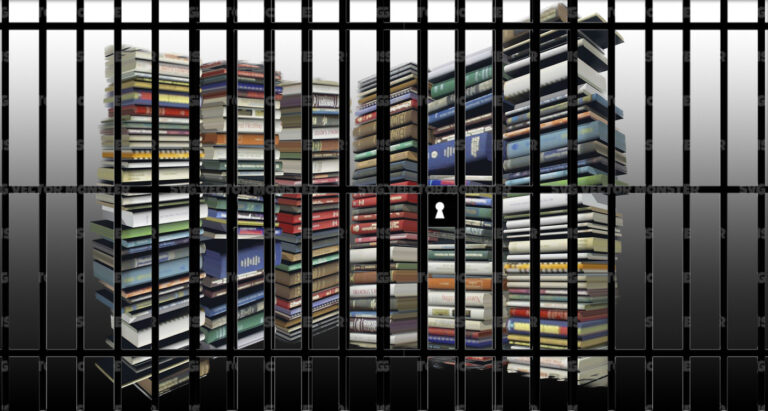

The sinking of freedom

Australia is still going backwards on right to know.

Prime Minister Kevin Rudd’s refusal to answer questions about the causes of a fire on a boat carrying refugees echoes the secrecy of the children overboard scandal of the Howard era.

Australians’ hopes for a new era of openness and accountability are fading as the new government fails to reject the culture of secrecy or promote the debate to bring Australia into the 21st century with a bill of rights.

Memories of lies about refugees throwing their children overboard, media images of refugee prisoners behind razor wire and a raft of unanswered questions about 353 asylum seekers who drowned on SIEV X during the Howard government years will always link asylum seekers with issues about the right of Australians to know what is happening in crucial areas of government.

Australians believe that they are entitled to freedom of speech but there is no express provision for this under the Australian Constitution.

Dr AJ Brown, Professor of Public Law at Griffith University, notes that “…the Australian public is still catching onto the fact that the rights that they assume they have are not as well protected as they might assume.”

He believes that the current discussion about a National Bill of Rights framework is vital in educating the Australian public, who some would say have been too relaxed about asserting their rights.

Australia is the only liberal democracy in the world without its own constitutional protection, bill of rights or charter protecting freedom of expression.

“I think freedom of speech suffers from the great Australian complacency and the fact that Australia has never had to, or bothered to, protect its freedoms,” says author, arts critic and journalist Diana Simmonds.

“Complacency is the Australian disease: she’ll be right is just not good enough, although politicians love it.”

Renowned QC and human rights activist Australian-born Geoffrey Robertson was in Sydney last month to promote his new book a Statute of Liberty that takes the practical step of laying the groundwork for a draft law. A strong advocate for a Bill of Rights in Australia, he argues that “Australia needs a bill of rights to reclaim its gold medal reputation for free speech and human rights” and that at present freedom of speech is merely a fragile implication from the constitution.

“We must write down clearly the entitlement of every citizen in the only way that politicians and public servants will understand and respect: that is they must be written into law,” he writes in the book.

Geoffry Holland, barrister and media law lecturer in the Faculty of Law at the University of Technology Sydney, agrees. “There are those who argue that there is no need for an entrenched protection of speech as we are able to rely on democratically elected parliaments to not unreasonably restrict speech. Unfortunately this is not the case.

“In recent years governments (both Federal and State) have imposed restrictions that generally go beyond what is necessary to achieve the government’s desired purpose, but with no entrenched protection parliaments have passed the restrictions with no (or little) debate about the proper limits of the restrictions,” he said.

But Andrea Durbach, public interest lawyer and Director for the Australasian Human Rights Centre (AHRC), is not so pessimistic about our current situation.

“I don’t think there is a significant censorship in Australia compared with other countries in the world. I don’t think we’re very bad at all . . . what people perceive as freedom of speech is relative,” she says.

“But there is room for improvement in our Freedom of Information laws absolutely.”

The Freedom of Information argument has particular implications for Australia’s media. Australia is currently ranked 28th on the press freedom index Reporters Without Borders list, below Namibia, New Zealand, Jamaica and Lithuania, suggesting that there are still many blocks from to a free flow of information in Australia. The Reporters without Borders committee particularly criticised the heavy sentences in anti-terror legislation which mean that a journalist who interviewed a person suspected of terrorism risks going to prison for up to five years.

But the limits to freedom of expression in a raft of anti-terrorism laws passed with little debate during the Howard years is just part of the problem. In 2007 an Independent Audit of Free Speech in Australia – the Moss Report – noted that are “about 500 pieces of legislation which, to one degree or another contain ‘secrecy’ provisions or restrict the freedom of the media to publish certain information’. Mark Scott, ABC’s managing director recently emphasized this, saying “Once governments, businesses and other institutions put up the brick walls, denying the public good information – and the knowledge that extends from it- the democratic system we value ceases to function.”

In 2007, Australia’s major newspapers, television and radio networks joined forces to launch Australia’s Public Right to Know Campaign. It represents a serious commitment by Australia’s most powerful media to protect public access to information. This year their recent conference focused on the need for protection of journalists and whistleblowers, privacy laws and the public’s right to be informed of government intentions and actions. And it was at this forum that Special Minister of State Senator John Faulkner chose to announce long awaited improvement to the Commonwealth Freedom of Information (FOI) act.

Before the 2007 Federal election, the ALP promised that should they be elected they would make changes to freedom of the press and the public’s access to information which would constitute a “significant restructure of information laws” and Faulkner’s announcement seems to indicate that the Rudd Government intends to live up to the hype. Two of the biggest problems were that few people could afford to pay the FOI charges and Ministers could simply decide not to apply FOI by using what was called a ‘conclusive certificate.”

In the largest overhaul of the Act since it was passed in 1982, Senator Faulkner outlines the changes we can expect and what this will mean for open government, democracy, and journalists. The changes will see applications for information under the act now free of charge and a new independent office of information commissioner will be set up to help process them. It will be much harder for Ministers to block FOI applications. The proposed changes to the Act come after a decade of new security and sedition laws under the Howard Government, laws that restricted what could be made available in the public sphere and threatened the freedom of journalists and public servants with arrests and possible jail sentences.

Generally the media and public bodies have welcomed the changes to the FOI Act. But Australia still faces some daunting barriers to freedom of information and speech. Peter Timmons, FOI expert and Deputy Chair of the Independent Audit of Free Speech in Australia, says the reforms do represent significant incremental change but limited rethinking of the basic concepts.

“What we will end up with is hardly an access to government information act tailored to community needs and expectations and reflecting 21st century realities . . . it’s still essentially the 1982 Act – in fact drafted in the 70s – with a lot of legalisms and horse and buggy features of the original,” he says.

“The Minister clearly sees the draft legislation as something to wave in front of the public service as evidence that the government is serious about culture change.”

Geoff Holland, of UTS, also has some doubts. “Whilst the amendments to the law do appear to indicate that the Rudd Government is prepared to meet their pre-election commitment to reform FOI so as to remove many of the limitations on access to information that currently exist it will only be when the final Bill to be put to the Parliament is revealed will the full extent of the reforms become apparent,” he said.

But it is not only current FOI laws that may impede freedom of the press. Commercial and political interests also appear to play a major role, particularly in the arts and the recent incident that occurred between student journalists at the University of Technology and the Sydney Writers’ Festival (SWF) highlights this.

The dispute over the alleged censorship of its UTS-produced official daily newspaper – The Festival News – thrust the issue of free speech into the limelight. The newspaper has run for years, until last year when the first edition of Festival News was temporarily impounded, and distribution of the following three editions was hindered, allegedly because remarks made about senior figures in the NSW Government which was the major sponsor of the event, were deemed to be derogatory. The Festival News will not be appearing in 2009 as SWF has issued a statement which said: “We have been unable to find a mutually satisfactory way forward with UTS.”

In her article about the affair in Crikey, Wendy Bacon, Professor of Journalism at UTS, examines the potential problems about how much influence the Festival sponsors should be able to exert over the content of its program, and whether the SWF has become the “creature of publishers and sponsors to detriment of serious engagement and open discussion”.

Padraic Cannon, a UTS journalism/law student and a member of the executive of the UTS Journalism Society, said that there is a relationship that exists between art and critique, and neither sponsors nor the sensitivities of event organisers should intrude.

“In this instance the sponsor that was ‘offended’ was the government, so I think that the Festival organisers overreacted – governments are fair game for the media in any democratic society.”

Arts journalist Diana Simmonds agrees. She says corporate and government sponsorship of the arts is affecting the whole arts sector. “In the past it wasn’t such a problem, there was a clear understanding that advertising and sponsorship did not impinge on editorial independence. That has been steadily eroding in the mainstream media in recent years.”

Geoff Holland also believes that corporate sponsorship can and does influence the outcomes of the things sponsored.

“The same can often be said about Government sponsorship of the arts, particularly in times of economic conservatism when governments demand accountability in all expenditure of public monies,” he said

There is no doubt that the role of journalists, writers and publishers in understanding complex issues on national and international politics has become globally important and challenging. But Australia is still entrenched with cultural problems in the public sector that act against the release of information. Until there is a strong enough push for transparency and constitutional rights, we will still have to push for our freedom of speech.

By Emma Kemp