He shadowed Martin Luther King to the mountaintop

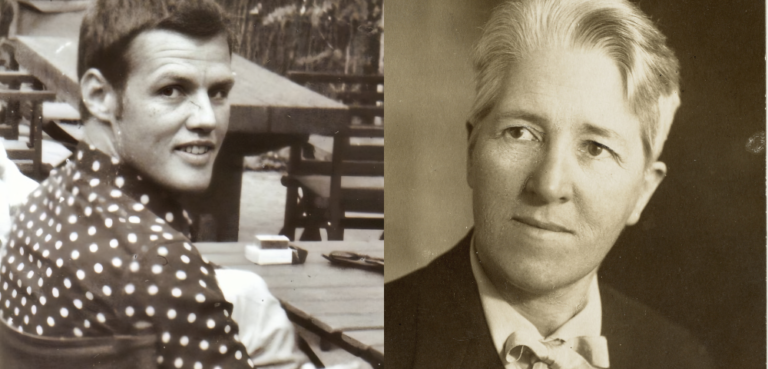

Ernest C Withers. He was the black photojournalist who, way back in the 1960s had instant access to everybody who mattered in the US civil rights movement. His photos of the key incidents and leaders of that turbulent time are classics. But all along he was a spy for the FBI, a footsoldier in J. Edgar Hoover’s “domestic intelligence” and dirty tricks program.

We now know this thanks to a nice piece of investigative journalism by The Commercial Appeal, a daily paper from Memphis Tennessee.

It’s a classic case really. Withers had been trained as a photographer in the US Army. In 1948 he was hired as a city police officer, along with eight other African Americans who were Memphis’ first black cops. Three years later he was fired for taking bribes from a bootlegger. Tellingly, he was never charged. We may surmise that in return he struck a Faustian bargain with the FBI.

According to the Appeal, “Many political informants from the civil rights era were unwitting, unpaid dupes. Yet Withers, who was assigned a racial informant number and produced a large volume of confidential reports, fits the profile of a closely supervised, paid informant, experts say.”

After losing his job as a cop, Withers fell back on photography and by the early 1950s, he was well established in the black community as a professional photographer, chronicling the blues scene, weddings, church socials, sporting events and the increasingly restive civil rights movement.

Some old participants in the movement, shocked by the revelation that the greatly respected photojournalist was a spy, have tried to downplay Withers’ betrayal as a sort of minor personal failing, motivated by the need for money to support his large family. As they tell it, everything in the movement was “open” anyway. There was nothing Withers could have told the FBI that would have made a difference to anything and in any case, the FBI was supposed to be protecting civil rights leaders from violent white racists so inevitably, you had to talk to them.

This is hopelessly naïve bunkum because Hoover’s FBI wasn’t just passively collecting information on US citizens. It was snooping for a sinister and anti-democratic purpose. The agency ran a covert operation, called COINTELPRO (short for counter intelligence program), that attempted to disrupt “radical” movements – including King’s moderate Southern Christian Leadership Conference – with dirty tricks. They leaked embarrassing details of leaders’ personal lives to the media, targeting individuals with radical views for prosecution and got them fired from their jobs. It’s likely they went further.

What the FBI feared was not so much that the black community’s fight against segregation and discrimination was destabilising American politics but that eminently non-violent and “reasonable” black leaders, like King, were groping towards conclusions about the nature of American capitalism that were leading them to oppose the war in Vietnam and US policy in Latin America and they were made even more edgy by the alliance between King and trade unions representing black workers.

In a 1967 speech, King pointed to the irony of American blacks fighting and dying for a country which treated them as second class citizens:

“We were taking the young black men who had been crippled by our society and sending them eight thousand miles away to guarantee liberties which they had not found in Southwest Georgia and East Harlem… We have been repeatedly faced with the cruel irony of watching Negro and white boys on TV screens as they kill and die together for a nation that has been unable to seat them in the same schools.”

King was a dead man walking. On March 29, 1968, he went to Memphis in support of black sanitation workers striking for higher wages and better treatment. Withers was at the Memphis airport to meet him and he shadowed the civil rights leader the day before his murder and reported a meeting King had with black militants to his FBI handlers.

On that day King gave his famous “I’ve been to the mountaintop” speech.

“I would like to live a long life. Longevity has its place. But I’m not concerned about that now. I just want to do God’s will. And He’s allowed me to go up to the mountain. And I’ve looked over. And I’ve seen the promised land. I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the promised land. And I’m happy, tonight. I’m not worried about anything. I’m not fearing any man. Mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord.”

King was shot at the Lorraine Motel at 6.01 the following evening. They said the assassin was an addled drifter called James Earl Ray and that he had acted alone, but many people smelled a rat. In 1999, King’s widow, Coretta, along with the rest of his family, won a wrongful death claim against one Loyd Jowers and “other unknown co-conspirators”. Jowers claimed to have received $100,000 to arrange King’s assassination. A jury of six whites and six blacks found him guilty, and that government agencies were party to the assassination.

• For the Commercial Appeal’s exposure of Withers: http://www.commercialappeal.com/withers-exposed/